As cellists, we've long been told by teachers to "sit up straight," "don't squeeze the instrument," and "keep your shoulders relaxed." The received tradition passed down through generations of pedagogues has shaped our approach to the cello. But what if I told you that scientific research is now proving that our predecessors got it right—and revealing exactly why these traditional teachings work so well? In this post, we examine historical treatises on posture and cutting-edge research in acoustics and biomechanics to understand why posture matters and how to optimize it for improved sound quality, enhanced technical ease, and reduced risk of injury.

1. From No-Endpin Foundations

Early cellists, such as Jean-Louis Duport (1749-1819), supported the cello between their calves without an endpin, using leg bracing and torso alignment to stabilize the instrument. French conservatoire methods emphasized sitting on the chair's edge with one foot forward, maintaining a "noble, upright" stance that balanced stability with freedom of the bow hand. These early innovations have influenced modern cello technique by promoting an upright posture and a "square" hand position, both of which are essential for advanced technique.

2. The Endpin Revolution

The mid-19th-century adoption of the adjustable endpin liberated the cello from the constraints of calf grips, allowing players to rest the cello on the floor. Lifting devices had existed since the 18th century, but modern endpins standardized during the 1890s enhanced acoustic resonance and reduced tension, unlocking more virtuosic techniques and repertoire. Adrien-François Servais (1807-1866) is recognized as an early, not the first, adopter of endpin use.

3. Modern Biomechanics

Elevating the cello off the floor requires adjusting the body accordingly, which affects how the muscle groups are engaged. Recent motion-capture studies reveal that accomplished cellists naturally rotate their torsos slightly to the left (5° at rest, up to 16° when reaching the highest strings) to align the bowing arm and minimize awkward reaches. EMG measurements—"muscle microphones"—show that a straight spine channels weight through the skeleton, reducing back-muscle effort and freeing strength for bow control. In contrast, slouching forces the back muscles to compensate, stealing power from the arms. Good posture, then, is not just elegant; it's mechanically superior.

4. Acoustics Discoveries

The endpin not only allows a more upright sitting position but also frees the cello from the leg cradle. Sound-measurement tools confirm why "not squeezing" the cello matters. Pressing the knees too firmly against the ribs acts like damping pads on a speaker cone, muffling overtones between roughly 900 Hz and 10 kHz. Easing off just an inch of leg pressure can restore brightness and projection: the left knee governs higher-frequency sparkle, and the right knee controls lower-frequency warmth. Thus, many cellists know the trick of squeezing the cello with their legs to dampen a wolf tone as a temporary fix. Finding that stable yet light contact lets the wood vibrate fully, producing tone with both clarity and depth.

5. A Practical Five-Step Posture Assessment

1. Body-Type Mapping: Determine your leg-to-torso ratio. Short legs/long torso keep knees level with thighs; long legs/short torso lower knees slightly for better bow-hand reach.

2. Endpin Calibration: Adjust the height so your bow arm swings freely without lifting or collapsing your shoulder. The cello's bridge should align near your sternum without forcing back extension.

3. Angle Fine-Tuning: Tilt the cello slightly right (5°–10°) so your bow hand accesses the upper strings without overreaching. If using a Tortelier-style endpin, test angles incrementally.

4. Leg Contact Modulation: Experiment by reducing knee contact by 1–2 cm increments. Listen for increased amplitude in long tones and richer overtones, especially on D and G strings.

5. Dynamic Check-Ins: Pause periodically during practice sessions to realign the spine with the shoulders and reassess knee contact. Observe yourself occasionally to check the consistency of torso rotation and bow-arm freedom.

Cellists today benefit from scientific research that sheds light on long-held wisdom. By incorporating the stability principles of Duport's era and modern findings in biomechanics and acoustics, cellists gain a holistic posture strategy that serves sound, technique, and health, bridging centuries of cello wisdom with today's scientific clarity.

Adrien-François Servais, shown with a cello and short endpin

French cellist Paul Tortelier (1914-1990), inventor of the Tortelier endpin, which angles more towards the floor

Bernhard Romberg (1767-1841), German cellist and composer

Friedrich Dotzauer (1783-1860), German cellist and composer

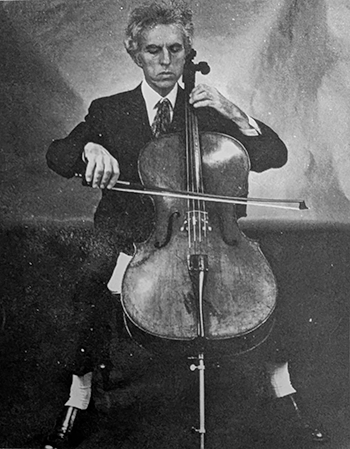

Mstislav Rostropovich playing the Duport Stradivarius with a long endpin and high shoulder flexion (1978)

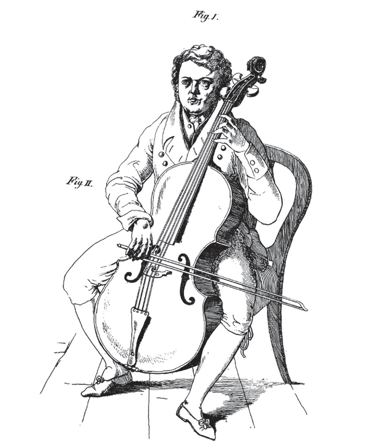

Jean-Louis Duport playing the cello upright without an endpin, using a low bow arm (1788).