I still remember flipping through Alwin Schroeder’s 170 Foundation Studies as a kid with trepidation and puzzlement. I could not understand why anyone would write such repetitive torture with so little musical incentive. Furthermore, why would anyone want to play them week after week? Years later, teaching drew me back to the etude shelf, and research revealed something remarkable: the best etudes far transcend academic exercises; they are musical vignettes drawn from the composer’s active performing life. Sebastian Lee’s career exemplifies this perfectly.

Lee’s performing career directly shaped his compositional approach. From 1837 to 1843, he served as principal cellist at the Paris Opéra, where his tenure coincided with the Paris premieres of Giselle, Berlioz’s Benvenuto Cellini, Donizetti’s La favorite and Les martyrs, and Weber’s Le Freyschutz. The broad set of musical skills and sensibilities developed at the Paris Opéra, including assorted bow techniques, intonation, phrasing, and harmonic understanding, all appear in his etudes. This design was not a coincidence; it was an intentional approach born from practical performance settings..

Born in Hamburg, Sebastian Lee (1805-1887) was four years older than Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847), a fellow native of the same city. He learned the cello from Johann Nikolaus Prell, a central figure of the Hamburg School and pupil of Bernhard Romberg. After debuting in Hamburg, Lee toured Leipzig, Kassel, and Frankfurt before arriving in Paris in April 1832, where he achieved immediate success at the Théâtre-Italien, a hub for Parisian high society frequented by writers such as Stendhal and Balzac. After his tenure at the Opéra ended in 1843, he joined the teaching staff of the Paris Conservatoire, where he remained until 1868, when he returned to Hamburg. This progression from Hamburg training to European touring and success in Paris created the foundation for his unique pedagogical approach.

Lee’s revolutionary teaching method emerged directly from his performance experience. His “Méthode pratique pour le violoncelle” (Op. 30), dedicated to Louis-Pierre Norblin (1740–1854), his predecessor at the Paris Opéra, aimed to guide novices safely through their first steps and protect them from bad habits. Ingeniously, the method pairs students and teachers in cello-duo formats, so that ensemble playing, listening, voicing harmonic progression, and phrasing are practiced from the first lessons rather than being added later. This design mirrors the varied performance settings he had to navigate

Lee’s musical network reinforced this collaborative approach. His two younger brothers supported his ensemble-focused pedagogy. Louis achieved fame as a cello “child prodigy of Hamburg.” Maurice pursued a career as a pianist in Paris and London. Sebastian and Maurice collaborated on works such as “Gavotte Louis XV” and “Pearls of the Day,” performing together in chamber concerts at Salle Pleyel, organized by Charles Dancla, with whom Lee later became a colleague at the Paris Opéra and the Conservatoire. These chamber concerts emphasized the intimate and dynamic musical communication in contrast to the grand and sweeping gestures in operatic literature.

Lee’s 131 opuses prove this point perfectly—they function as musical vignettes of these divergent musical settings. His Fantasies and Variations on famous operatic arias condensed entire acts into salon pieces. According to researcher Pascale Marin, these arrangements, including Grande Fantaisie dramatique on Meyerbeer’s Le Prophète (Op. 53), functioned as musical trailers for grand opéra, popularizing their repertoire beyond theatre walls while showcasing Lee’s creative paraphrase and technical command. One can easily recognize in his 40 Melodious and Progressive Etudes, Op. 31 the same lyricism found in Romantic opera arias. Recent recordings by Martin Rummel (2017, Paladino Music) and a flourishing of YouTube videos demonstrate how Lee’s etudes still speak to today’s cellists.

This compositional method serves a pedagogical purpose: technical proficiency is developed to meet the musical requirements (as a means) that it serves as an end. For example, Op. 31, No. 18 is a study on detached bowing, involving precise, short bow strokes. The repetitiveness can be appreciated as an exercise in relaxed bow arm and mental focus; more importantly, the study encourages honing bow strokes to shape rising and falling arpeggial passages into musical phrases. These skills provide excellent preparation for tackling more demanding pieces like Popper’s Elfentanz and Elgar’s Cello Concerto.

Lee’s contributions to cello performance and pedagogy were equally recognized in his native Germany. In December 1885, Friedrich Grützmacher reached out to Julius Klengel in Dresden to arrange a collective tribute for “the old gentleman” on his 80th birthday. This gesture underscores Lee’s esteemed status as a “national treasure” among German cellists, a sentiment suggested by Marin’s recent archival work.

For modern teachers, Lee’s works offer a template for developing technical skills while stimulating musical sensibility. Begin each etude by singing the line to engage with it fully. Identify the implied harmony and mark where phrases break to indicate breath points. Let these musical choices guide your technical decisions—bow distribution, shifts, and articulation should serve the phrase, not override it. When techniques are organized around musical purpose, they stick naturally and transfer more effectively to repertoire.

Sources and links

Sebastian Lee Association (https://sebastianlee.org/)

Martin Rummel performs Lee’s Opp. 31 and 70

https://www.discogs.com/release/11499278-Sebastian-Lee-Martin-Rummel-Etudes-For-Cello-Op-31-Op-70

A copy of the first edition (1842) of Methode pratique pour le violoncelle bearing the stamp of the Bibliotheque Royale

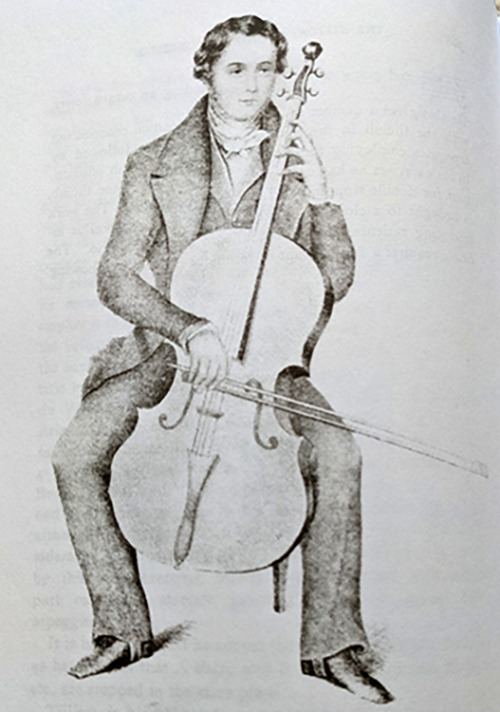

Sebastian Lee, circa 1843