If Fingerings Could Talk

A personal reflection on fingerings and bowings in my musical genealogy

GREAT HERITAGE

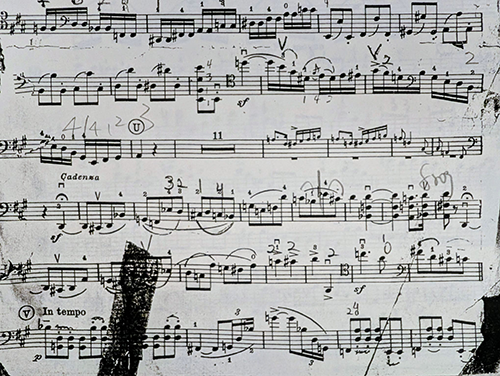

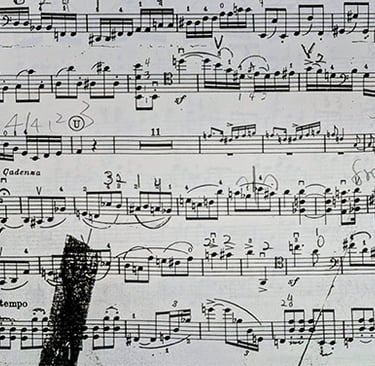

A few years ago, while reorganizing my music library, I unearthed my old score of the Schumann Cello Concerto. The pages were adorned with fingerings, bowings, and scattered reminders in my teacher Zara Nelsova’s markings. The note 'On the string,' inscribed above the A minor run near the end of the first movement, instantly drew me back to her studio, her voice echoing in my mind, her Marquis de Coberon Stradivarius looming just feet from my music stand. These faded yet untidy markings felt like sacred relics, preserving the essence of my musical journey and serving as artifacts of a pedagogical lineage that stretches back through generations of great cellists.

I found myself reluctant to erase them, even though I no longer use those same fingerings and bowings. They had become part of my musical genealogy.

The Genealogy of Musical Intent

This discovery led me to consider fingerings more philosophically. We often approach fingerings and bowings pragmatically. Which choice avoids an awkward shift? Which ensures better intonation, and which facilitates safer shifts? These are essential considerations. But what if we considered more probing questions: Why did they choose this fingering or bowing in this passage? What musical vision were they serving?

Nelsova’s fingerings in my Schumann weren’t just technical roadmaps; they embody her musical ideals. In quite a few places, she deliberately uses separate bows on slurred notes printed in the score to create excitement and momentum. In the last movement of the Brahms F major Sonata, Ms. Nelsova suggested going up the G string to play the arpeggiated triplets (with “full bow hair” handwritten in the score). That would not be my first choice of fingerings because the passage is in piano, and the most logical and convenient fingerings would be to stay in the lower positions on the D and A strings. So, her choice spoke volumes about the sonority she sought in those two sets of triplets! In other places, she would redistribute the bow to sustain a fuller tone to carry the long, slurred phrase. These choices reflect her idea of good sound and rich tone, attested to in all her performances and recordings. Not all of her choices can indeed be adapted with ease on my part. Yet, I have the most profound respect for her relentless commitment to serving the music, even in the most technical passages. To me, it was always music that came first, never the other way around.

When we examine how great musicians select their fingerings and bowings, we see what they value in their music through the choices they make. Each shows a decision about the character, mood, and emotional direction they want to convey.

Entering Another’s Musical World

To adopt another musician’s fingerings and bowings is to contemplate a relationship with their musical ideals. When I played those Schumann passages using Nelsova’s markings, I was temporarily inhabiting her musical consciousness, feeling how she conceived the phrase’s architecture, experiencing her aesthetic priorities through my fingers. Mind you, I am not always successful, as I have very different physical attributes, and Ms. Nelsova’s command over the cello was pure mastery.

I recall another incident with a different cello teacher at grad school, who asked me to study the fingerings used by students of a renowned pedagogue, specifically their approaches to the Haydn D Major Concerto. My initial reaction was indignant. “I’m here to study with you,” I thought. "Why are you sending me to learn from someone else’s students?" The suggestion felt to me like laziness on that teacher’s part, or at least it sounded like an admission that the famous pedagogue was somehow superior.

Years later, I began to realize the purpose of that assignment. That teacher wasn't undermining his own approach; he was showing me a way to enter into the musical worlds of others. Only by understanding different fingering philosophies could I develop a truly comprehensive understanding of how technique serves music. Clinging exclusively to one pedagogical tradition, however convenient the method or glamorous its history, creates artistic myopia.

This fallacy goes far beyond celebrity worship or blind imitation. Leonard Rose’s fingerings for the Beethoven sonatas possess a logic of elegance and clarity that may not evoke the overt passion in Rachmaninoff’s sonata. Piatigorsky’s same-finger, half-step shift in Schelomo reveals his dramatic intensity and yearning, unsuitable for Haydn. Each artist’s choices reflect their unique relationship with the music and their understanding of it.

The danger lies not in studying or using these approaches, but in adopting them without understanding. When we follow Piatigorsky’s fingerings simply because they were Piatigorsky’s, we miss the profound musical logic behind his choices. The real question becomes: What musical vision does this fingering or bowing serve? This understanding is crucial in making our interpretive choices more meaningful and personal.

The Mirror of Musical Identity

This reflection leads to the most searching question of all: Do I share this musical vision? Sometimes the answer is yes. We discover that another artist’s approach resonates deeply with our own musical instincts. At other times, we realize that while we can appreciate their logic and the convenience of straightforward adoption, it doesn’t align with our interpretive goals.

This isn’t about right or wrong; imitation can be the sincerest form of flattery until one’s artistic identity is completely subsumed. Your fingering choices become part of your musical voice, as unique as your vibrato or your approach to musical timing. The young cellist who slavishly copies a master’s markings will eventually need to ask: Which of these choices truly serve my musical vision? Which reflects who I am becoming as an artist?

The evolution from following to choosing to creating is the essence of musical maturation.

As I carefully returned my marked Schumann score to the shelf, I realized those faded pencil marks weren’t just technical annotations; they were family letters from one generation of musicians to the next, messages across time about the profound intimacy between artist and art. In preserving them, I honour not just Nelsova’s legacy, but the continuing conversation between generations of musicians, each adding their voice to an ever-continuing musical dialogue.

What story do your fingerings tell about your musical journey?